This article appeared in Knife Magazine in July 2022.

Know Your Knife Laws – The Pocket Clip Conundrum

By Daniel C. Lawson, Attorney and Knife Expert

Whether “pocket clip carry” – a knife clipped to a side pocket along the trouser seam – is concealed or open carry is an ongoing controversy. The issue extends to knives clipped to a pocket on a purse or handbag. It is especially troublesome for people in the seventeen states where concealment is determinative as to what type or size of pocket knives may be carried with confidence that one is not violating a concealed carry restriction.1

In California, any folding or collapsible knife having a blade that locks in the open position is a “dirk or dagger” and may not lawfully be carried concealed. Dirks and daggers are widely understood everywhere else to be fixed blade instruments typically carried in a sheath. If a person in California casually slips a lockable folder into a pocket, he risks a conviction punishable by up to one year in jail.

Rhode Island and Delaware, for instance, prohibit the concealed carry of any pocket knife having a blade longer than three inches. In Nebraska and Colorado, the allowable blade length for any concealed pocket knife is 3 and 1/2 inches.

Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Oregon are among states where concealed carry of any automatic knife is prohibited.

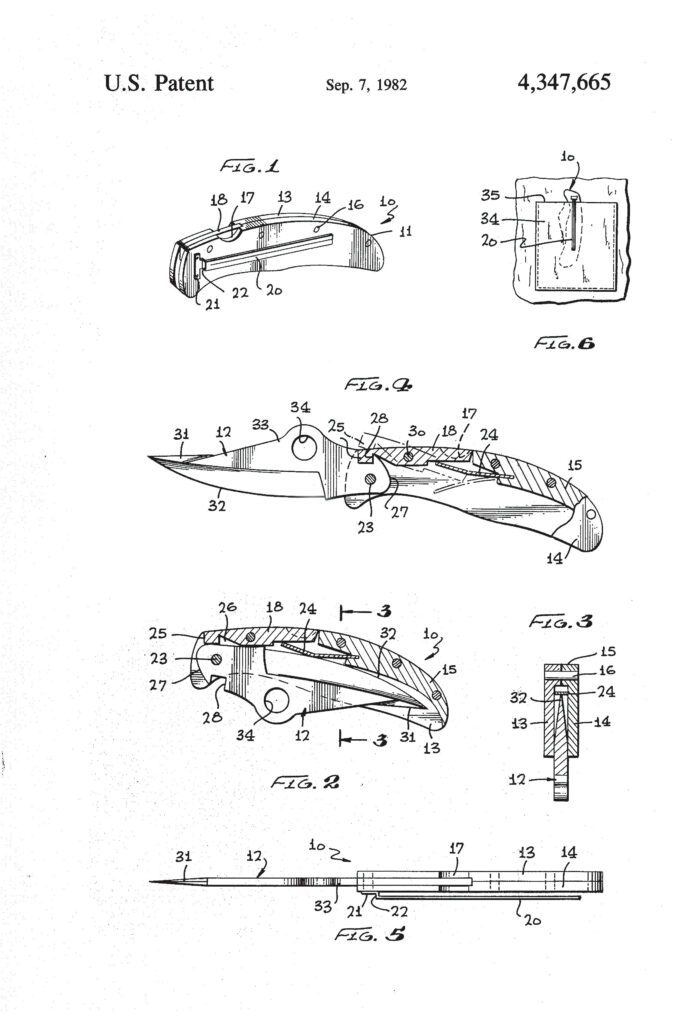

In the above examples, a restricted knife would likely be concealed if carried within a pocket (which is how most of us carried pocket knives before the early 1980s when Sal Glesser, Spyderco, devised the pocket clip). Concealment was not a factor. Spyderco’s first model, named “Worker,” was a practical one-hand operable tool for everyday hard use.

Concealed carry restrictions pre-dated the pocket clip and were not intended to apply to pocket knives. In 1838, Alabama enacted a concealed carry restriction on “any species of firearms, or any Bowie knife, Arkanskas [sic] toothpick, or any other knife of the like-kind, dirk, or any other deadly weapon.”

Two hundred years ago, the Kentucky Supreme Court in Bliss v. Commonwealth 12 Ky. 90 (1822) reversed a conviction under an act that provided:

any person in this commonwealth, who shall hereafter wear a pocket pistol, dirk, large knife, or sword in a cane, concealed as a weapon, unless when travelling on a journey, shall be fined in any sum not less than one hundred dollars.

The class of restricted items described by “dirk” and “large knife” clearly did not apply to pocket knives.

Those 19th-century concealed carry laws intended to curb dueling and “honor” based armed eruptions were routinely upheld when challenged on Constitutional grounds with the reasoning that the restriction did not preclude the bearing of arms but merely regulated the manner in which arms were carried. The decision of the Alabama Supreme Court in the 1840 case of State v. Reid, 1 Ala. R. 612, which focused on the Alabama State Constitution, is an example:

We do not desire to be understood as maintaining, that in regulating the manner of bearing arms, the authority of the Legislature has no other limit than its own discretion. A statute which, under the pretence [sic] of regulating, amounts to a destruction of the right, or which requires arms to be so borne as to render them wholly useless for the purpose of defence [sic], would be clearly unconstitutional. But a law which is intended merely to promote personal security, and to put down lawless aggression and violence, and to that end inhibits the wearing of certain weapons, in such a manner as is calculated to exert an unhappy influence upon the moral feelings of the wearer, by making him less regardful of the personal security of others, does not come in collision with the constitution.

The insidious process of “mission creep” during the 20th century extended the restrictions to a class of convenient cutting tools intended for convenient carry in a pocket. Laws originated to restrict the concealed carry of large, fixed-blade knives, now applied to pocket knives of modest size, which are only awkwardly not carried concealed. How does a man or woman openly carry a simple, slip-joint pocket knife? Why a man or woman would need or want to carry a knife is not relevant.

Effective July 1, 2022, the Virginia restriction on the sale and possession of automatic knives is removed, although it remains unlawful to conceal carry such a knife in the state. VA Code Ann. § 18.2-308 provides as pertinent:

If any person carries about his person, hidden from common observation, (i) any pistol, revolver, or . . . any dirk, bowie knife, switchblade knife, ballistic knife, machete . . . he is guilty of a Class 1 misdemeanor. . . For the purpose of this section, a weapon shall be deemed to be hidden from common observation when it is observable but is of such deceptive appearance as to disguise the weapon’s true nature.

The original Virginia concealed weapon statute, enacted in 1838, provided the violation would occur:

if any person shall hereafter habitually or generally keep or carry about his person any pistol, dirk, bowie knife, or any other weapon of the like-kind, from this use of which the death of any person might probably [sic] ensue, and the same be hidden or concealed from common observation.

Numerous items, including automatic knives, have been added over the years. The qualifying words “habitually or generally” have been removed.

The case of Richards v. Commonwealth, 443 S.E.2d 177 (1994) may be helpful in evaluating how a Virginia court would address the issue of pocket clip carry of an automatic knife. A police officer named Royer was investigating an incident where one Randy Richards was the victim:

Royer observed an object sticking one-half to three-quarters of an inch out of Richards’s right back pants pocket. Royer further testified that he did not know what the object was and asked Richards to identify it. When Richards told Royer that the object was a knife, Royer asked Richards to remove it from his pocket. (Underlining supplied)

The knife was an inoperable automatic with the blade fixed in the open position. Richards was charged with a violation of § 18.2-308 and found guilty in a non-jury trial. The judge concluded the knife was a “dirk” and ruled that while the knife was not concealed – as part of it was visible – the handle was “deceptive in its appearance as to disguise the weapon’s true nature.” The judge did not explain the deceptive aspect.

The Virginia Court of Appeals reversed, stating, “Nothing about the appearance of the handle suggests that it is anything other than a knife.” The Court further suggested that “disguise” would require some deceptive appearance, such as a knife that resembled a belt buckle or fountain pen.

The Richards case, by analogy, would suggest that it is sufficient if the item may be identified as a knife based on the visibility of some portion thereof. If a portion of a knife handle is visible, it may be assumed to be a knife. It should not be necessary in a pocket clip carry situation that one be able to distinguish an automatic knife from a manual knife.

It is essential that some part of the knife remain observable or such that it may be seen. In the year after the Richards decision, the same Court upheld a conviction where a handgun carried in a man’s rear pocket with the handle extending above the edge was concealed by the duffle bag slung over his shoulder as he walked along the side of a road. The Virginia Court of Appeals in Main v. Commonwealth 457 S.E.2d 400 (1995) stated:

If the gun was in the defendant’s right rear pocket and its handle, the only part extending outside of his pocket, was covered by the duffle bag, the weapon was hidden from common observation. It was hidden from all except those with an unusual or exceptional opportunity to view it.

A coat, sweater, vest, apron, or untucked shirt that obscures the otherwise exposed pocket-clipped knife would, by analogy, cause concealment. Given the realities of climate, weather, dress codes, style, decorum, and modern life, whether a knife clipped to one’s pocket is concealed is often in flux.

The original Virginia concealed statute version with the “habitually or generally” language allowed for occasional concealment, provided it was casual rather than one’s habit or common practice. The Main v. Commonwealth case mentioned above may have reached a different outcome under the original 1838 statute.

The objective of concealed carry restrictions, as stated by the Alabama Supreme Court in the 1840 case State v. Reid mentioned above, was that a concealed weapon “is calculated to exert an unhappy influence upon the moral feelings of the wearer.” The North Carolina Supreme Court stated in the 1968 decision of State v. Gainey 160 S.E.2d 685 that:

The purpose of the statute is to reduce the likelihood a concealed weapon may be resorted to in a fit of anger. In case of an altercation, one who has a pistol concealed about his person will be less likely to act with restraint than if he were unarmed.

Knives are inanimate objects incapable of exerting influence – unhappy or otherwise – on one’s “moral feelings” or of controlling human behavior. Placing a pocket knife into a handbag or pocket has no disinhibiting effect. This should be patently obvious when concealment may fluctuate based on the drape of one’s clothing.

AKTI provides information on the issue of concealment in state laws on our website. Some slight variation exists among those states that restrict the carry of pocket knives based on concealment. The pocket clip on a knife is a relatively new development. It has not been the subject of review by appeal-level courts apart from “probable cause” cases where law enforcement officials have asserted that a pocket-clipped knife constituted a basis for a search. These cases do indicate that pocket-clipped knives are sometimes “noticed” by law enforcement officers.

The issue of concealment is typically an issue of fact to be decided by the jury or the judge in a non-jury trial. How the factfinder will decide is difficult to predict. For example, a California statute provides that a knife carried openly in a sheath suspended about one’s waist is deemed not concealed. The case of In re Alfredo S. 208 Cal. Rptr 794 (1984) involved a folding knife with a 4-inch long locking blade carried in a pouch worn on a belt. The pouch was partially covered by a sweatshirt. The trial judge stated:

Due to the nature of the sheath in which a knife was found, the Court makes the specific finding that even if that were worn on a belt with no shirt on whatsoever, that that [sic] would be a concealed knife.

The above “finding” was reversed on appeal. AKTI suggests that the knife community should not be exposed to such vagaries and is working to eliminate such arbitrary laws.

Learn more about knife laws and how AKTI advocates for changes for the benefit of the knife community in the Resources and Legislation sections of our website.

__________

1Pocket knife concealed carry restrictions based on type or blade length obtain in the following states, CA, CO, DE, FL, IA, LA, MD, MS, NC, ND, NE, NM, OR, RI, VA, VT, and WV.