This article appeared in Knife Magazine in March 2021.

The Federal Switchblade Act – Is it Constitutional?

By Daniel C. Lawson, Attorney and Knife Expert

A prior article in this series examined the question of knives as arms that one may keep and bear.1 In this article, we examine whether the restrictions imposed on automatic knives by the Federal Switchblade Act (FSA) are constitutional, given the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Those restrictions are not insignificant of consequences. The FSA provides a penalty of up to five years imprisonment and or a fine of up to $2,000 for a violation.

The first occasion the Second Amendment was considered by the U.S. Supreme Court was in the case of United States v. Miller, 307 U.S. 174 (1939), which involved a sawed-off shotgun and a very superficial acknowledgment of a “well-regulated militia.” The Miller decision is widely misunderstood as holding that the protection of the Second Amendment does not extend to weapons popularly believed to be used by criminals, such as a weapon typically associated with criminals: sawed-off shotguns, blackjack, brass knuckles. Rather, the Supreme Court stated:

In the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a ‘shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length’ at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly, it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment or that its use could contribute to the common defense.

The first sentence in the above quote states that there is no evidence on the issue of whether sawed-off shotguns are related to a “well-regulated militia.” The second sentence states that the Court cannot simply assume or employ its “judicial notice” of such a relationship. In other words, the Supreme Court said it cannot decide, and it remanded or sent the case back to the Arkansas District Court.

The history of Jackson “Jack” Miller and the peculiar nature of the case of U.S. v Miller is the subject of a scholarly review by Brian L Frye.2 Essentially, Miller was a career criminal gang member and well known to state and federal authorities in Oklahoma. In April of 1938, he was stopped while traveling between Oklahoma and Arkansas and had a sawed-off shotgun in his possession. The National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA) required that one pay a tax of $200 for such an item. (It still requires the same $200 tax if one desires to acquire a “silencer.”) Miller had not paid the tax, and he was charged with violating the controversial NFA, which had not yet been tested in court. The District Court Judge, who had advocated enthusiastically for federal firearms restrictions as a U.S. Congressman before becoming a judge, declined to accept Miller’s plea of guilty and appointed lawyer Paul Gutensohn to represent Miller. On January 3, 1939, Gustensohn filed a demurrer to the charge, which essentially stated that the NFA was not a genuine revenue or tax law. Rather, it was an infringement on arms prohibited by the Second Amendment. The Judge immediately granted the demurrer and dismissed the case. The next day, Gutensohn was appointed by the Arkansas Governor to fill the seat of a state senator who had died several weeks earlier. The U.S. Attorney, also an advocate for the NFA, filed an appeal and further requested a bypass of the Court of Appeals so that the matter could proceed directly to the U.S. Supreme Court. This extraordinary request was granted, and Gutensohn was so advised by a letter from the Supreme Court clerk dated March 15. The oral argument was set for March 31.

The “fix was in.” Miller obviously lacked the resources or incentive to appear before the Supreme Court. Gutensohn had neither the time nor the funding to respond. The U.S Attorney would be unopposed. On May 15, the Supreme Court issued a short opinion that discussed militia history but stopped short of a definitive holding and remanded the case back to Judge Rogan:

We are unable to accept the conclusion of the court below, and the challenged judgment must be reversed. The cause will be remanded for further proceedings.

The matter was moot as Jack Miller’s corpse with four bullet wounds had been found near Chelsia, Oklahoma, six weeks earlier on April 4, 1939. There were no further proceedings. The NFA survived as a tax and was touted as a crime-fighting measure that would frustrate only criminals.

While U.S. v Miller’s decision was “awkward,” it was the state of 2nd jurisprudence in 1958, and it suggested some need for a “link” between an arms restriction and a well-regulated militia. Miller hinted that a restriction would be constitutional if it concerned the efficacy of the militia.

The outcry in the 1950s, led by Senator Kefauver (D-TN), was not universally endorsed for federal switchblade legislation; many considered it unnecessary, if not dubious. The chief law enforcement officer at the time, U.S. Attorney General William Rogers, along with many others, opposed it. Kefauver’s bill failed at least once to pass. What was needed was a bill that would frustrate only teens and young adults theatrically brandishing “switchblades.” The primary constitutional concern was a valid basis for Federal jurisdiction. A $200 tax on switchblade knives for anyone under the age of 25 was not feasible, and many resisted the notion that the knives were only used by criminals.

What eventually passed and was signed into law by President Eisenhower as Pub. L 85-623, popularly known as the “Federal Switchblade Act,” prohibited the manufacture or introduction of “switchblade” knives into interstate commerce except for the military, the militia, or the “activities” of governments, including state and local. It is presented in a way that these broad exceptions are not obvious.

The easily found portion of the Federal Switchblade Act consists of §§ 1241 through 1244 of Title 15 Commerce and Trade. § 1244 originally contained exceptions for the Armed Forces and persons having “only one arm.” A sub-section in a different “Title” which prohibits using the Postal Service to ship poisons, explosives, “live scorpions,” and poisonous animals; expressly allows knives having a blade which opens automatically. . . to be conveyed in the mails:

(1) to civilian or Armed Forces supply or procurement officers and employees of the Federal Government ordering, procuring, or purchasing such knives in connection with the activities of the Federal Government;

(2) to supply or procurement officers of the National Guard, the Air National Guard, or militia of a State ordering, procuring, or purchasing such knives in connection with the activities of such organizations;

(3) to supply or procurement officers or employees of any State, or any political subdivision of a State or Territory, ordering, procuring, or purchasing such knives in connection with the activities of such government; and

(4) to manufacturers of such knives or bona fide dealers therein in connection with any shipment made pursuant to an order from any person designated in paragraphs (1), (2), and (3).

The above quote is from 18 U.S.C. § 1716 (g) and is part of Pub. L 85-623. Long-established rules of statutory interpretation require that all parts of a single legislative act on a specific issue be construed together. § 1716 (g) is part of the FSA, and the entities described therein are exempt from its restrictions.

Note that in 15 U.S.C. §§ 1241-1244, the inelegant term “switchblade” is used, but in § 1716 (g), where the same knives are destined for the militia and anybody in government, the wording shifts to “knives having a blade which opens automatically.”

Most, if not all, U.S. states have laws that provide that every able-bodied individual above a certain age are members of the militia. South Carolina § 25-1-60. captioned Composition and classes of militia is representative and provide that essentially all “able-bodied persons over seventeen years of age” are members of the militia consisting of three classes, one of which is the “unorganized militia.” Federal law, 10 U.S.C. § 311, captioned Militia: composition and classes, provides that “all able-bodied males” aged 17 to 45 who are not in the National Guard are in the “unorganized militia.”

A strong argument can be made that the FSA was unconstitutional even under the dubious and misinterpreted U.S. v Miller “standard.” The argument is more compelling in light of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in District of Columbia v Heller 554 U.S. 570 (2008), which was the first in-depth review of the Second Amendment by that body.

Heller clearly held that the “right” protected is an individual right and guarantees a right to carry weapons:

Putting all these textual elements together, we find that they guarantee the individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.

Heller also considered what types of arms may be prohibited and applied a “dangerous and unusual” test in finding that a handgun was a protected arm. The FSA provides that automatic knives are legal and available for a large class (all government employees) without restriction for “activities.” The wording of the FSA negates that the knives are dangerous or unusual. The essential “problem” to be addressed by the restriction on interstate commerce was that automatic knives were too common.

It may be asserted that an automatic knife’s ease of operation renders it readily deployable and, thus, dangerous. Heller points out that one-hand operability is a valid safety consideration in the case of handguns:

it is easier to use for those without the upper body strength to lift and aim a long gun; it can be pointed at a burglar with one hand while the other hand dials the police.

Automatic knives were stigmatized in the 1950s by popular culture, with assistance from a few opportunistic politicians. Even then, Congress recognized that automatic knives were useful tools, hence the broad § 1716 (g) exceptions for state and local activity and its militia speed bump.

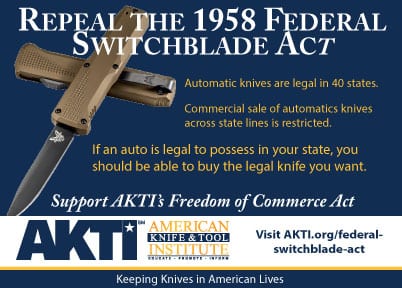

The Federal Switchblade Act’s legislative history indicates that it was intended to assist the various states with restricting automatic knives. It is now widely recognized that the supposed switchblade menace was a harmless fad. Complete restrictions applicable to automatic knives remain in only six U.S. States. The American Knife & Tool Institute (AKTI) continues to seek repeal of these state restrictions. We also continue our efforts to repeal the improvident and unconstitutional Federal Switchblade Act.

You can learn more about what the Federal Switchblade Act is, AKTI’s efforts to repeal it, and the knife laws in your state and where you work or travel. Sign up to receive AKTI’s emailed news of legislative initiatives and information to give you the confidence to carry the knife and edged tool of your choice and join or support AKTI’s efforts on behalf of the entire knife community.

_____________________

1Lawson, Daniel C., “Knives as Arms,” Knife Magazine, November 2020, 37, 46 and www.AKTI.org.

2Frye, Brian L., “The Peculiar Story of United States v Miller,” New York University Journal of Law & Liberty, 2008, Vol. 3, No. 1., 48-82.