This article appeared in Knife Magazine in March 2023

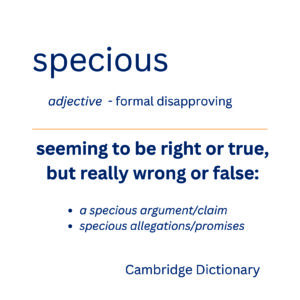

Know Your Knife Laws – Specious in Seattle

by Daniel C. Lawson, Attorney and Knife Expert

A severe restriction on the public carry of knives in the City of Seattle has been protected for decades by questionable rulings emanating from small majorities of the Washington Supreme Court. Those rulings are a tangled web which, when unraveled, is recognized by the high court of that state that aspects of Washington knife law violate the state and federal constitutions.

A severe restriction on the public carry of knives in the City of Seattle has been protected for decades by questionable rulings emanating from small majorities of the Washington Supreme Court. Those rulings are a tangled web which, when unraveled, is recognized by the high court of that state that aspects of Washington knife law violate the state and federal constitutions.

The Seattle Municipal Code defines “dangerous knife” as “any fixed-blade knife and any other knife having a blade more than 3 1/2 inches in length.” Section 12A.14.080 of that code captioned “Unlawful use of weapons” states as pertinent that it is unlawful to:

Knowingly carry concealed or unconcealed on such person any dangerous knife.

Two unrelated prosecutions for dangerous knife possession led to a consolidated appeal to the Washington Supreme Court. Fixed-blade knives were involved in both cases.

Defendant Alberto Montana was arrested for “drug traffic loitering” and found to be in possession of a paring knife with a blade three inches in length. Defendant Henry McCullough was arrested for theft and found to be in possession of a knife with a blade six to nine inches in length which was further described as a fish-filleting knife with a duct-taped handle.

Criminal use of the knives by either defendant was neither alleged nor a factor. The drug trafficking and theft offenses were not an issue upon the appeals.

Both defendants raised the Right to Bear Arms provision of the Washington State Constitution as a defense to the possession charges. That part of the Washington State Constitution, Art. 1, § 24 reads:

The right of the individual citizen to bear arms in defense of himself, or the state, shall not be impaired, but nothing in this section shall be construed as authorizing individuals or corporations to organize, maintain or employ an armed body of men. (Underlining supplied).

While the Seattle Municipal Court convicted both defendants, the King County Superior Court reversed both convictions by holding that the Seattle ordinance did indeed violate the Washington Constitution.

The City of Seattle did not accept that decision and sought review and relief. The plurality decision by the Washington Supreme Court in the City of Seattle v. Montana, 919 P.2d 1218 (1996) reinstating the convictions is troubling. While the decision was some 14 pages long, less than half a page addressed the basis for the appeal – whether the knives carried by Montana and McCullough were “arms.”

The Washington Court acknowledged several cases from other states, including a case involving knives as “arms” State v. Delgado, 692 P.2d 610, (1984) decided by the Oregon Supreme Court. In that case, Delgado presented the issue of the scope of “arms,” and the constitutional guarantee similar to that of Washington: The Oregon Supreme Court in Delgado undertook actual analysis:

Our analysis in Kessler of the meaning of the term “arms” is central to the case at bar and so merits a further discussion. We reasoned that because settlers during the revolutionary era used many of the same weapons for both personal and military defense, the term “arms,” as contemplated by the constitutional framers, was not limited to firearms but included those hand-carried weapons commonly used for personal defense. . .

A kitchen knife can as easily be raised in attack as in defense. The spring mechanism does not, instantly and irrevocably, convert the jackknife into an “offensive” weapon. Similarly, the clasp feature of the common jackknife does not mean that it is incapable of aggressive and violent purposes. It is not the design of the knife but the use to which it is put that determines its “offensive” or “defensive” character.

The Delgado case was on point, but evidently not what the Washington Supreme Court wanted. It seized upon an obscure 19th-century case from Louisiana to support the proposition that the subject knives were not “arms.”

However, that Louisiana case neither supported that conclusion nor involved the Louisiana Constitution. Rather, the State v. Nelson case simply held that a Louisiana statute restricting the concealed carry of bowie knives, pistols, dirks, and other “dangerous weapons” did not apply to the razor carried by the defendant:

The word “arms” did not appear anywhere in the Louisiana statute. The Washington Supreme Court included a quote from the Louisiana case:

Only “[i]instruments made on purpose to fight with are called arms.” State v. Nelson, 38 La.Ann. 942 (1886).

The above quote from State v. Nelson case was distorted and incomplete. Moreover, the misquote did not represent the holding of the court. Instead, the words were from the prosecution brief arguing that razors should be “weapons” within the prohibition. The Court rejected that suggestion. The actual passage reads:

The definition quoted in the brief of the Attorney General, from Worcester, is conclusive against the State. It is: Instruments made on purpose to fight with are called arms, or weapons, such as are accidentally employed to fight with, weapons.” A legitimate deduction from this is that a razor belongs to the latter class, i. e., such as are accidentally employed to fight with, and not to the class of instruments “made on purpose to fight with.” The razor might be a weapon if accidentally or actually employed to fight with-as in State v. Lowry-but it certainly is not such a dangerous weapon as is contemplated by the statute.

The prosecution asserted that razors are sometimes accidentally used for fighting and should be restricted under the other dangerous weapon residual clause. The State v. Nelson case held that razors were not specified in the statute and were not perceived as being in the same class as dirks, Bowie knives, and pistols. The case is not precedential authority for the proposition, as claimed by the Washington Supreme Court in Montana.

The agenda on the part of that court in City of Seattle v. Montana is discernible. The convictions were reinstated. Only four of the nine justices endorsed to lead opinion, although the others concurred with the result.

An opportunity to correct the City of Seattle v. Montana (“dumpster fire” of a decision) was presented several years later by the case of City of Seattle v Evans 66 P.3d 906 (2015). One Wayne Evans was operating a motor vehicle at an excessive speed and was stopped by a police officer. That officer observed “furtive movements” as he approached the car and smelled marijuana. Evans had a fixed blade knife with a plastic sheath in a pocket.

Evans was charged with a violation of §12A.14.080 – Unlawful Use of weapons – the same offense in the Montana case. A few profoundly significant rulings regarding the right to bear arms occurred in the intervening years.

The 2008 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in District of Columbia v Dick Heller 554 U.S. 570 held that the 2nd Amendment guarantees an “individual right to possess and carry weapons in case of confrontation.”

The Heller decision included an analysis of what was encompassed by the noun “arms.” It quotes several 18th-century definitions:

Timothy Cunningham’s important 1771 legal dictionary defined “arms” as “anything that a man wears for his defence, or takes into his hands, or useth in wrath to cast at or strike another.” 1 A New and Complete Law Dictionary; see also N. Webster, American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) (reprinted 1989) (hereinafter Webster) (similar).

The term was applied, then as now, to weapons that were not specifically designed for military use and were not employed in a military capacity.

The linchpin of the 1996 Seattle v. Montana (paring knife) decision was the distorted quote: only instruments made on purpose to fight with are called arms. As mentioned above, Wayne Evans, the speeding motorist with a small, fixed blade knife, challenged the Seattle municipal ordinance on state and U.S. Constitutional grounds. Evans had been convicted of violating §12A.14.080, captioned “Unlawful Use of weapons.” That section was part of Chapter 12A.14 of the code captioned “Weapons Control.” The Heller decision by the U.S. Supreme Court completely discredited the arms/weapon dichotomy proffered by the Washington Court.

A five to four majority of the Washington Supreme Court unabashedly suggested that Evans had misread Heller:

Evans relies on language in Heller asserting that the term “arms” encompasses “weapons that were not specifically designed for military use and were not employed in a military capacity.” Heller, 554 U.S. at 581. He is correct that the Second Amendment protects the right to possess weapons designed for personal protection as well as for use in a militia.

The U.S. Supreme Court did not state, in any way, that the Second Amendment protected only weapons designed for personal protection of use in a militia. Instead, it unequivocally stated the “Second Amendment does not protect those weapons not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes.” Knives, including paring knives, are commonly possessed for lawful purposes.

The simple majority of the Washington Supreme Court shamelessly suggested Evans had misread the Oregon Delgado case mentioned above, as well as the DeCiccio case by the Connecticut Supreme Court:

Evans also relies on DeCiccio and Delgado to reinforce his argument that all fixed-blade knives are arms. Neither case supports that interpretation: both cases rely on an extensive historical and functional analysis of the specific knife at issue, and DeCiccio expressly limits its holding to “knives with characteristics of the dirk knife at issue in the present case. . .. The lengthy historical analysis and specific limiting language of both opinions actually undermine Evans’s argument and reinforce our conclusion that some knives are not arms. (Citations omitted).

While the quote claims both cases involved “extensive historical and functional analysis of the specific knife at issue,” no such similarity existed.

The knife at issue in Evans was claimed to be a paring knife. The DeCiccio case involved a knife with a 5.5 inches doubled-edged blade with a cross-guard, which the Connecticut Supreme Court held was constitutionally protected. It also stated, “we do not consider whether the right to keep and bear arms under the second amendment extends to other types of knives.”

While the Delgado case involved a “switchblade” and ruled that such knives are constitutionally protected, the analysis as quoted above suggested “kitchen” knives were also protected; actual use rather than design was determinative as to defensive or offensive “character.”

A famous and poignant aphorism comes to mind – “Oh what a tangled web we weave / When first we practice to deceive,” clearly applies to the Montana and Evans majority decisions by the Washington Supreme Court. They wanted to preserve the draconian Seattle Municipal Code and were willing to misrepresent the holdings of other courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court.

In doing so, they endorsed the holding of the Oregon Supreme Court in Delgado, which is that “switchblade” knives are constitutionally protected. They similarly endorsed the Connecticut Supreme Court DeCiccio decision holding that “dagger” is constitutionally protected. It is generally unlawful to simply possess a “spring blade knife” under Washington state law. Moreover, the public carry of “dirks” and “daggers” is profoundly restricted under state law.

The American Knife & Tool Institute (AKTI) suggests that very few knives are designed exclusively for weapon use. Such a knife would be an extravagance for many of us. The Constitutional threshold is the common use for lawful purposes. Any other interpretation would incentivize, if not require, the carry of knives to be restricted to types with highly evolved weapon characteristics. It would allow courts such as those in Washington to invent silly distinctions and inject a level of uncertainty calculated to discourage the exercise of the right.

We further suggest that knives are bearable as arms and commonly possessed for routine lawful purposes. Knives are the base technology in the history of human existence. They have been essential to our subsistence and preservation/defense for thousands of years. Knives may indeed be the quintessential bearable arm.

For reliable knife law information, additional detailed articles to understand knife laws, and follow the initiatives of the American Knife & Tool Institute, visit our website AKTI.org.